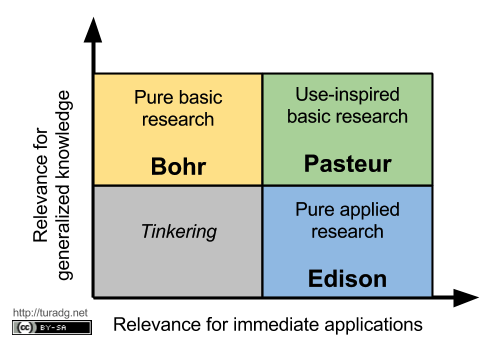

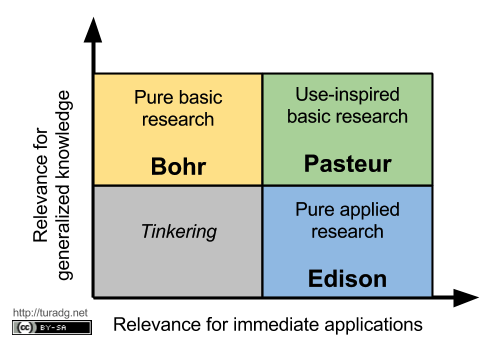

If you’ve been to an plenary session or keynote on education research chances are you’ve heard of Pasteur’s Quadrant. It’s the idea that basic science (e.g., Bohr) and applied science (e.g., Edison) can be brought together to have significant impact on society, as exemplified in Pasteur’s prodigious contributions. Which quadrant should education research target? Pasteur’s Quadrant was articulated (and I believe originated) in the book of the same name by Donald Stokes in 1997. Stokes was a professor of politics and public affairs and argued for use-inspired basic research as an important target of public funds. My interest is more in research than public policy and I haven’t read the book. If you’re interested, but the publisher’s summary gives a good summary of the public policy thesis and the transitions in government research funding that it spoke to.

Education research, to my eyes, is still finding and defining itself. After Dewey, the greatest advances were by the psychologists. That would be “basic” research in education. While we learned a lot about how people learn, little of it made it into classrooms. Other education research was unscientific, with anthropological or post-modernistic perspectives. There wasn’t much education science and the little that there was was quite basic. The No Child Left Behind act shook this all up. (Quick poll: do you pronounce NCLB as en-see-el-bee or nickleby? I met someone recently who calls it nickleby.) Part of the act formed the Institute for Educational Science within the Dept of Ed. “Educational Science,” now what does that mean? The first director of IES, Grover (Russ) Whitehurst, in a speech describing the mission of IES, cited Pasteur’s Quadrant. But he went further and called for IES to focus on Edison’s Quadrant. It’s worth a read. (I think this is fair use…)

One way of making this distinction is in the terms introduced in the infrequently read but oft cited 1997 book by Stokes, called Pasteur’s Quadrant – Basic Science and Technological Innovation. Stokes described three categories of research based on two binary dimensions: first, a quest for fundamental understanding, and second, a consideration of use. The work of the theoretical physicist, Niels Bohr, exemplifies the quadrant in which researchers search for fundamental knowledge, with little concern for application. The research of Louis Pasteur, whose studies of bacteriology were carried out at the behest of the French wine industry, characterizes the work of scientists who, like Bohr, search for fundamental knowledge, but unlike Bohr, select their questions and methods based on potential relevance to real world problems. The work of Thomas Edison, whose practical inventions define the 20th century, exemplifies the work of scientists whose stock and trade is problem solution. They cannibalize whatever basic and craft knowledge is available, and conduct fundamental research when necessary, with choices of action and investment driven by the goal of solving the problem at hand as quickly and efficiently as possible.

|

Considerations of Use |

| Low |

High |

| Quest for Fundamental Understanding |

Yes |

Pure Basic Research (Bohr) |

Use-Inspired Basic Research (Pasteur) |

| No |

|

Pure Applied Research(Edison) |

Each of the scientific quadrants identified by Stokes is important to the common good. Those who argue for the value of basic research have no trouble finding examples of work inspired only by intellectual curiosity that turned out to be extremely practical. Bohrs’ work on quantum physics is a case in point. Without in any way diminishing the value of basic research, whether use-inspired or not, I want to argue for the importance of activities in Edison’s quadrant, particularly for topics in which there is a large distance between what the world needs and what realistically can be expected to flow from basic research, and for topics in which problem solutions are richly multivariate and contextual. Education is such an area: a field in which there is a gulf between the bench and the trench, and in which the trench is complicated by many players, settings, and circumstances. Choose what you consider to be the most exciting developments from basic research in Bohrs’ or Pasteur’s quadrants that are relevant to education. I’ll pick developments in cognitive neuroscience. Paint the rosiest scenario you dare for basic scientific progress in the topic you’ve chosen over the next 15 years. Then ask yourself what would need to be done to translate those imagined findings into applications that would have wide and powerful effects on education outcomes. I don’t know about you, but I’m not optimistic that the results of basic research, even if the findings are powerful, will flow directly and naturally into education. Goodness! Education hasn’t even incorporated into instruction what we know from basic research about the effects of massed versus distributed practice – and I learned about that in a psychology course I took in 1962. Yes, the world needs basic research in disciplines related to education, such as economics, psychology, and management. But education won’t be transformed by applications of research until someone engineers systems and approaches and packages that work in the settings in which they will be deployed. For my example of massed versus distributed practice, we need curricula that administrators will select and that teachers will follow that distributes and sequences content appropriately. Likewise, for other existing knowledge or new breakthroughs, we need effective delivery systems. The model that Edison provides of an invention factory that moves from inspiration through lab research to trials of effectiveness to promotion and finally to distribution and product support is particularly applicable to education. In summary, the Institute’s statutory mission, as well as the conceptual model I’ve just outlined, points the Institute toward applied research, Edison’s quadrant. I’ve labeled this chart, “Edison’s quadrant, mostly,” because I understand that it is important to nurture the development of basic knowledge related to education, particularly in areas in which other science agencies and major foundation’s aren’t involved. Thus, when resources permit, the Institute will support work that examines underlying process and mechanisms, and work that is initiated by the field. For instance, the President’s budget request for the Institute for fiscal year 04 includes a healthy amount of money for a field-initiated competition. In addition, many of our new funding programs that are squarely focused on application, such as our program in preschool curriculum evaluation, provide for grantees to carry out parallel research that examines underlying processes.

What do you think? I would love to hear your thoughts in the comments. Here’s another quote that might inspire you, Nikola Tesla speaking of Edison:

If Edison had to find a needle in a haystack, he would proceed with the diligence of a bee to examine straw after straw until he found the object of his search… I was almost a sorry witness of his doings, knowing that just a little theory and calculation would have saved him 90 per cent of the labor…

Incidentally, searching online, I see Pasteur’s Quadrant cited in ICT, chemistry and even geology. (Evidently, there is such a thing as applied geology.) Try those links if you want to know more about Pasteur’s Quadrant generally. And by the suggestion of my colleague Andrea Forte during the OLI Symposium 2008, there’s a Wikipedia article. Please improve upon it as I only made it last night. 😉